Health Care

Chase Corridor’s ‘Put up-Victimhood’ Storytelling – The Atlantic

[ad_1]

In his Surrealist Manifesto of 1924, André Breton wrote, “The marvelous is at all times lovely, something marvelous is gorgeous, in actual fact solely the marvelous is gorgeous.” That line got here to thoughts once I stood earlier than Mom Nature, a large canvas depicting a killer whale lifting a unadorned man into the air, eye stage with a flock of gulls. The picture was a spotlight of “The Bathers,” Chase Corridor’s standout debut on the David Kordansky Gallery in Chelsea this fall.

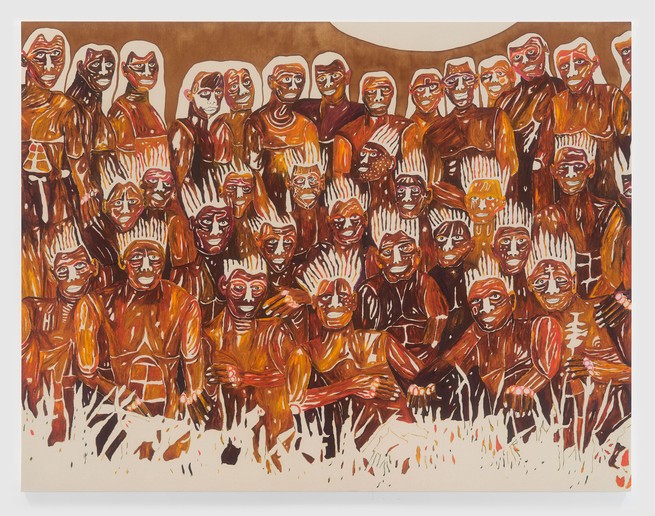

The present, of principally immense work priced from $60,000 to $120,000, was billed as an investigation into “nature, leisure, public area, and Black adventurism.” The playful and enigmatic scenes concerned males swimming, browsing, and generally levitating, in solitude or amongst a residing bounty of fish and birds. They had been without delay lovely and formally putting meditations on the richness and flexibility of a single colour: brown.

On the time of the exhibition, Corridor was on the cusp of turning 30. He floated by the gallery in a white tank and free grey slacks that broke over a pair of leather-based home sneakers, trying like a West Coast rapper from the G-funk period who’d not too long ago studied overseas in Florence. His aura was jubilant. The gang, filled with name-brand artists, collectors, and previous pals, appeared each taken by the art work and genuinely glad for the artist—two responses that don’t at all times mesh.

As not too long ago as three years in the past, Corridor was working odd jobs, scrounging free of charge supplies, dumpster diving for the stretcher bars from NYU college students’ cast-off canvases, discovering the indicators and symbols of his personal vernacular. Now he teaches on the college as an adjunct professor, and his work has landed within the everlasting collections of quite a few main establishments, together with the Brooklyn Museum and the Whitney.

In the course of the after-party for his opening, at a dive in Decrease Manhattan, Corridor slipped away from the gang to an empty stool beneath a flat-screen. The third set of the second males’s U.S. Open quarterfinal was taking place, Ben Shelton dropping to Francis Tiafoe. “Shelton’s gonna get it,” Corridor mentioned, smiling confidently, seconds earlier than the floppy-haired teenager ripped a cruel forehand down the road, saving the set and shortly snatching the match within the subsequent. I spotted my mixed-kid radar had failed me. It was solely by Corridor’s consideration that I recalled Shelton’s biography and noticed the tangled ancestry within the younger participant’s triumphant face—an ancestry like Corridor’s, like mine.

Conor Friedersdorf: Unraveling race

“Boy, you appear to be the climate!” is how a lady as soon as described Corridor’s personal tawny complexion because the solar bounced off it. The son of a Black father who was raised by his single white mom, Corridor had a peripatetic childhood, even spending his seventh-grade college 12 months in Dubai. After I first met him final spring—at a blue-chip artist’s opening the place it appeared like each different attendee I encountered, whether or not a collector, celebration hopper, or critic, needed to speak about Corridor—he spoke of his youthful self and the expertise of being a “Black” child with “white-looking” options as a form of racial “pimples” marring his look. As we speak, he notes an evolution, not solely in his creative observe however in his sense of himself on the earth. “During the last 10 years of actually attempting to navigate life and household and profession and mixedness,” he advised me, he’s been asking himself: “Am I the conduit for my very own expertise, or am I simply going to try to hope nobody says I’ve a white mother? It was like, ‘Why don’t I simply arise for my very own shit?’”

As James McBride as soon as wrote in The Coloration of Water, “being combined is like that tingling feeling you may have in your nostril simply earlier than you sneeze—you’re ready for it to occur but it surely by no means does.” You’re ready to develop into one factor or one other, however you by no means do. Corridor has chosen to embrace this irresolvable side of his identification, to not oversimplify it. He’s grappling with what he calls “these dichotomies of genetic disgrace and genetic valor”—enjoying with them by the juxtaposition of colour and blankness.

Corridor makes use of acrylic paint however primarily depends on an in depth scale of brown tones realized by the medium of brewed espresso. It’s an art-making course of he’s been tweaking since he was a young person in Southern California working after college at Starbucks, “smearing receipts” with doodles to deal with the boredom.

Over time, it has develop into a way of calibrating a complicated spectrum of beige, brown, and almost ebony tones. Darker browns are finer floor; lighter ones are coarser. By trial and error, and plenty of, many gallons of espresso, he’s developed 26 distinct hues out of a single bean and cultivated intensive relationships with the assorted baristas of his East Village neighborhood. He can simply buy 200 to 300 pictures of espresso in an outing, which his contacts have discovered to tug to his exact specs, and which he takes dwelling and applies to untreated cotton canvas by a way he describes metaphorically as “melanin being soaked into the cotton.”

Espresso beans and cotton bolls will not be simply representational opposites of lightness and darkness; they’re additionally emblematic of the legacies of Africa and Europe colliding within the New World by slavery. To today, these supplies characterize usually invisible ecosystems of poverty and coerced labor—smallholder farmers in Ethiopia, sweatshop staff in China. (The Brazilian artist Vik Muniz has additionally made artwork out of the supplies of the slave economic system—in his case, espresso beans and sugar.)

Corridor’s imaginative and prescient is achieved not solely by the melanated fields of expression he superimposes over whiteness by the method of, as he places it, “corralling and containing a water-based kind,” however to a major diploma by the preservation of uncooked open areas he pointedly leaves unpainted. Many of those voids of “conceptual white paint” are additionally interspersed inside his topic’s our bodies—white noses, kneecaps, even genitalia—making specific the base-level hybridity we’re conditioned to disclaim or gloss over.

It’s a method he has pursued to such lengths that, as he defined in a chat at Kordansky, he now owns a small a part of a craft-coffee firm. The espresso the viewers was gratefully sipping that morning within the gallery was derived from the identical supply that was used to make the encircling artworks. He spent three years growing a course of to reclaim even the grounds left over from the work, which he then changed into a collection of beautiful prints that went on show two blocks away at Tempo Prints the identical week as “The Bathers.” Nothing is wasted.

Regardless of his medium’s symbolism, and regardless of the arduous bodily labor that goes into making it artwork—the pouring and repouring of a crop-based liquid onto crop-based surfaces—the photographs that outcome will not be overtly political. This units him aside from many different minority artists he’s generally in comparison with (and from whom he attracts inspiration)—individuals similar to Henry Taylor—who’re thriving in a time of revived curiosity in figurative portray. His male topics are decidedly not responding to tragedy; they’re, he mentioned, “liberated figures outdoors of stereotypical Black areas.” In a portray known as Whitewash (Pelicanus Occidentalis), a ripped nude man stands astride a longboard. His face is drawn tight not with fear or heavyheartedness however with the deep focus of diligent focus: His solely battle is to stay vertical atop the water.

Corridor himself concedes that, when it comes to technical drawing, some NYU college students he teaches are extra succesful than he’s. However Rashid Johnson, one other Kordansky artist, advised me he sees in Corridor a younger painter with “an actual willingness to evolve and develop, and to construct a language.” Artwork, he says, is greater than “strokes on a canvas.”

Learn: Political artwork isn’t at all times higher artwork

The impact, each of Corridor’s particular person work and, in a extra profound method, of his cumulative work, is a refreshing problem. Corridor forces us to satisfy the individuals he depicts on their very own phrases, with out the same old lens—or crutch—of our inherited, fetishizing, or condescending projections.

One among his central targets, as he put it to me later, is “redefining our relationship with the panorama, outdoors of basketball, enslavement.” He’s involved with issues of company, world constructing, and individuality—what he calls “post-victimhood” storytelling. “I actually consider in life,” he advised me. “I am going out and attempt to make the very best of it.”

[ad_2]

Supply hyperlink